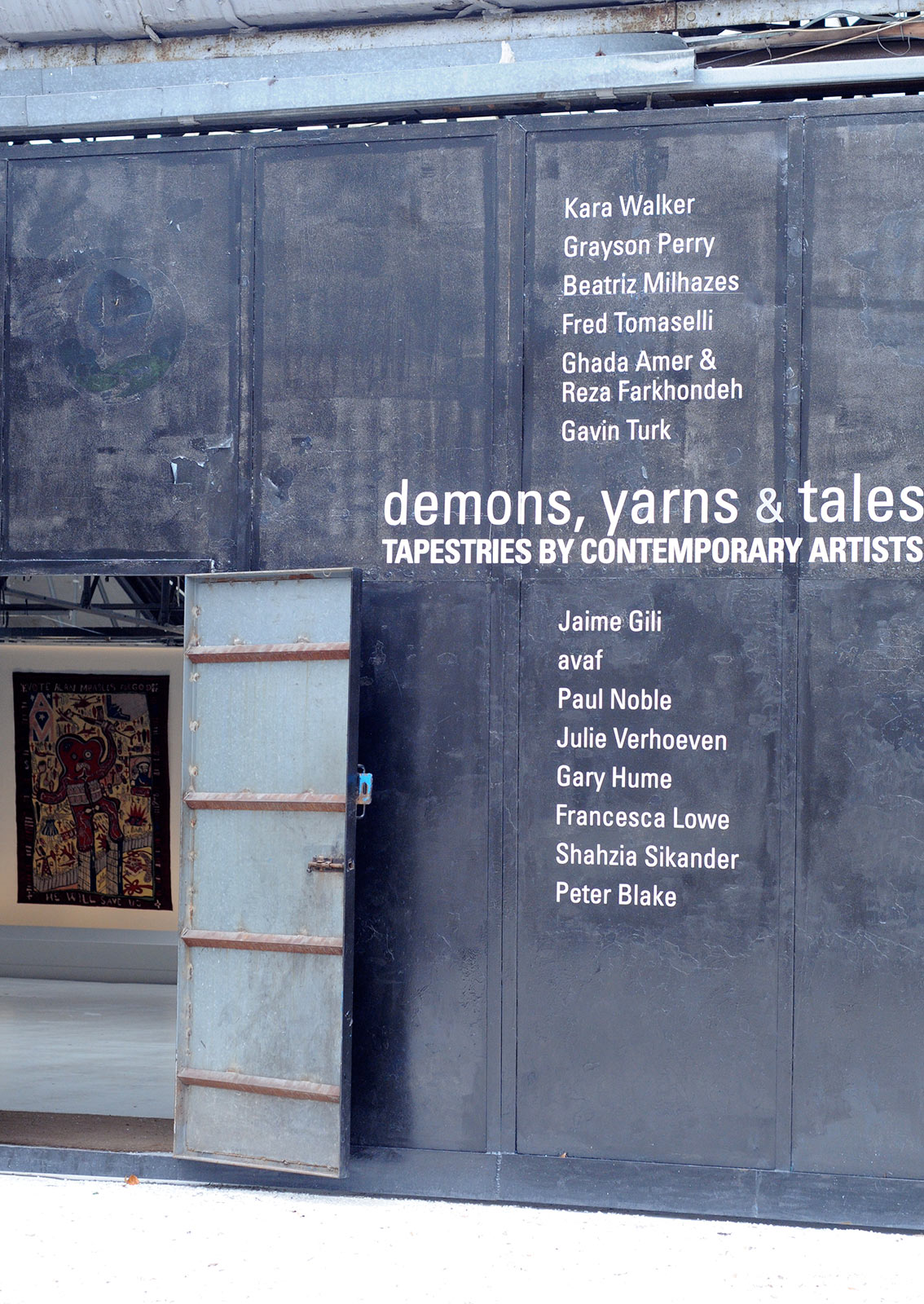

DEMONS YARNS AND TALES

The Dairy, London and travelling locations in New York and Miami

Curated by Christopher Sharp / Banners of Persuasion

Artists include: Gary Hume, Kara Walker, Avaf, Gavin Turk, Paul Noble, Fred Tomaselli, Beatriz Milhazes, Peter Blake.

From the curator’s introduction: “The exhibition is an experiment within the lost world of tapestry making, and addresses themes of translation and transformation. The works pose visual and tactile questions concerning the translation of meaning, and the exhibition reveals the shifting transformation of each artist’s unique visual style from his or her known medium into the uncharted and the unknown. The notion of tapestry, an art form with a complex and well-documented past, is transformed, enabling us to reconsider it as an illuminating and revelatory format for today's world.”

Introduction to Demons Yarns and Tales. By Sarah Kent

To be perfectly honest, I’ve never been much interested in tapestries; many have faded to monochrome echoes of their former glory, and this makes them hard to appreciate. Then there are the subjects – battles, treaties, hunting scenes and Biblical stories – which seem absurdly overblown in relation to the modesty of a medium which, despite its historical links with royalty and the aristocracy, has always struck me as essentially domestic. The simple truth is that I prefer paintings, and most other media. I’m a typical example, in other words, of pure prejudice.

Yet something about this project appealed to me. Of the fourteen artists taking part, most have no previous experience of designing a tapestry; nor is their work particularly well suited to the medium. I could easily imagine Beatriz Milhazes adapting her highly decorative abstractions for a woven design; yet her tapestry is a real surprise, because it is far more subdued in colour and shape than her paintings. How, though, would a maverick like Gavin Turk, who usually works in three dimensions, respond to such a challenge? His intriguing map of the world is the kind of oddball response that makes this project such a success. I was surprised to discover that many of the artists already had an interest in tapestry prior to their involvement in the project. Gary Hume, avaf and Julie Verhoeven, for instance, all mentioned their love of an exquisite group of mediaeval tapestries called ‘The Lady and the Unicorn’.1

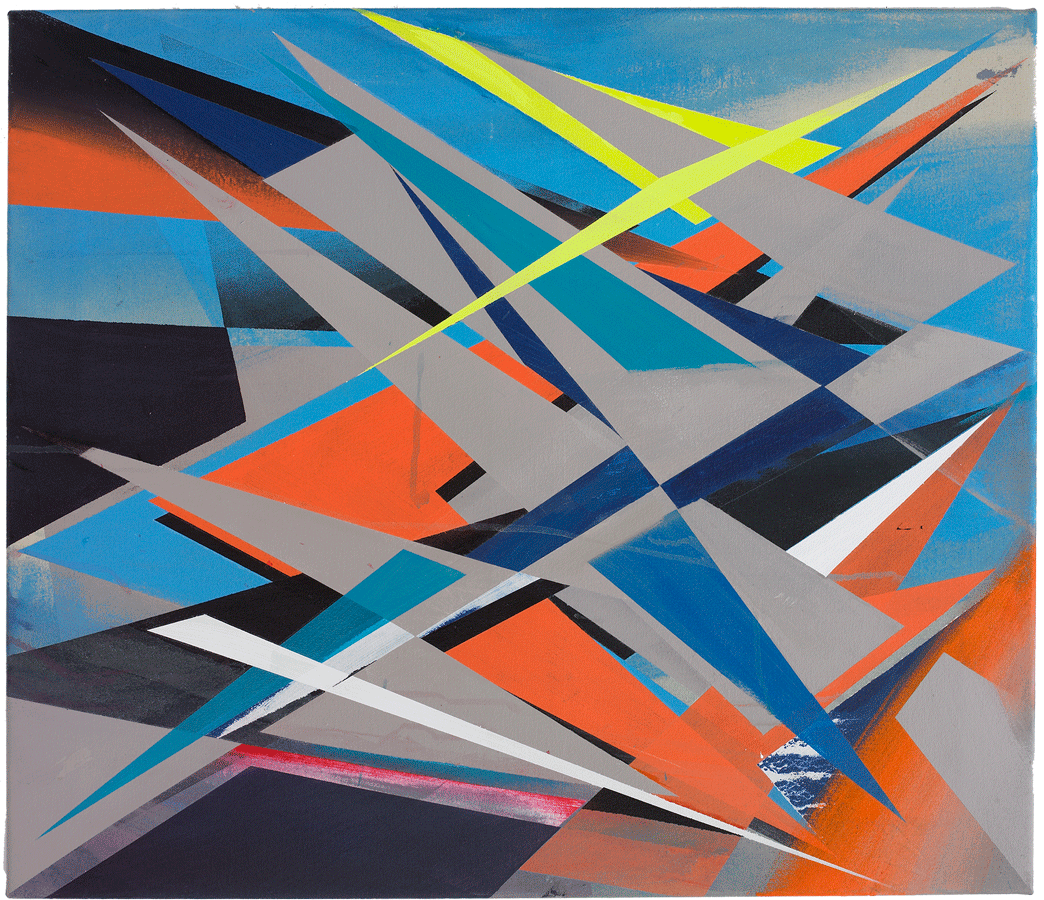

The artists invited to take part come from London, New York, Caracas, Rio de Janeiro and Paris; some know one another, but most do not. Their ages range from to 29 to 76 and their work differs dramatically from paintings (Ghada Amer & Reza Farkhondeh, Peter Blake, Gary Hume, Francesca Lowe, Beatriz Milhazes and Shahzia Sikander), to assemblages (Fred Tomaselli), sculptures and installations (avaf, Gavin Turk, Kara Walker), ceramics (Grayson Perry), prints, drawings and illustrations (Paul Noble, Peter Blake, Julie Verhoeven) and videos (avaf). It’s obvious from this list that no house style prevails; even among the painters, the work ranges from jazzy, hard-edged abstraction, to gauzy figuration and pop art.

I decided to speak to all the artists. I was curious to know how they set about making a design for a medium they had so little experience of, and if they felt their involvement in the project had been worthwhile. At the time of writing, some of the tapestries are still being made. When I talked to them, Gavin Turk, Ghada Amer and Kara Walker were waiting anxiously to find out how well their ideas would be translated, but everyone who’d seen their tapestries expressed delight at the quality of the finished product.

Ultimately, this is what made me want to write the catalogue. I was astonished by the perfection and beauty of the tapestries and overwhelmed by their fidelity to the original artwork or, where mimicry was impossible, by their inspired interpretation of the source material. This process of translation requires enormous skill. From the original artwork, a full-scale weaver’s graph has to be produced containing an outline drawing of the design, annotated with precise colour references for the weavers to follow. What a task!

With its infinitesimal variations on the colour grey, Paul Noble’s minutely detailed drawing must have presented an almost impossible challenge. Then there’s the problem of how to achieve diagonals and curves; because a tapestry is made from interlocking vertical and horizontal threads, it is virtually impossible to create curving or diagonal lines that don’t have a stepped profile. With its fleet of triangular shapes aligned on the diagonal, Jaime Gili’s painting could have been made for the express purpose of testing the weavers’ ingenuity. And with her web of interlocking arcs and circles, Beatriz Milhazes must have created similarly intractable problems. Yet in each case, the weavers have managed to produce clean, sharp outlines that, to the naked eye, appear absolutely fluent – not a zig-zag in sight! The weaving house making the tapestries is in China, where this is not a traditional craft. The company was set up only ten years ago and employs the Flemish weaving techniques used by the famous tapestry makers of Aubusson. It takes a long time to produce each tapestry partly because of the intricacy of the work, but also because the factory is situated in a rural community north of Shanghai and the weavers, all of whom are women, work part time so they can be free to help in the fields and gather in the harvest.

The inspiration for the project came from Christopher and Suzanne Sharp; they felt it was time to broaden their remit from rug design and chose tapestry because of its links with painting – because both canvases and tapestries hang on the wall and because, throughout the long history of the medium, artists have played a crucial role in making designs for tapestries. In the twentieth century, a revival of interest encouraged major figures such as Picasso, Matisse, Léger, Kandinsky, Braque, Ernst, Moore and Vasarely to produce tapestry designs and, in recent years, artists as diverse as Chuck Close, Craigie Horsfield and William Kentridge have undertaken large-scale tapestry projects. The medium, it seems, is here to stay. And, if the quality of these fourteen tapestries is anything to go by, it will continue to flourish.

1 The mediaeval cycle known as ‘The Lady and The Unicorn’ consists of six tapestries respectively titled ‘Love’, ‘Hearing’, ‘Sight’, ‘Touch’, ‘Smell’ and ‘Taste’. Featuring a lady, lion and unicorn in an exquisite formal garden, they are in the collection of the National Museum of the Middle Ages, Paris.

+ LINK: www.bannersofpersuasion.com